Culture

Found Footage: “Pretty In Pink”

Like many children of my generation and the generation before me, John Hughes partially raised me. If there are credits at the end of my life (which I hope won’t be nearly as long as the ones after The Dark Knight Rises), John Hughes will certainly get a mention in the Special Thanks. What I adored about his films were the ways in which he identified with and really understood young people, nailing their dialogue, foibles and mannerisms in the same way that Amy Heckerling and Lena Dunham would be proud of, and it’s almost hard to believe that a middle-aged, creepy, somewhat reclusive white dude wrote teenage girls so well. And many of these teenage girls would learn about growing up in his films in the same way that younger girls learned about periods from Judy Blume.

Personally, Hughes taught me a lot about the trials of falling in and out of love in your teenage years, including the very important lesson that you should never loan your underwear to a freshman. Through Long Duk Dong, I also learned what Asian racism was, and in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off I learned that you can be suddenly driving one way on the Dan Ryan Expressway in one shot and then the completely opposite way in the next. In this way, John Hughes helped me to realize that I could conquer the hormonal space-time continuum and maybe, just maybe, come back to school in the fall as a completely normal person, just like Molly Ringwald said I would. There was hope for me.

However, while penning classics such as Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club, Hughes has an incredible number of misfires on his resume—which we don’t talk about because he “changed our lives.” The 90s were especially unkind to him; during that decade, he was responsible for Home Alones 2 and 3, Baby’s Day Out, Dennis the Menace and Flubber, which Hughes and director Les Mayfield somehow got Marcia Gay Harden to agree to be in. But for me, the most egregious mark on Hughes’ record is actually one of his most beloved films: Pretty in Pink, a.k.a. that movie where the guy from Two and a Half Men spends two hours whining. Pink was the last John Hughes film I ever got around to watching, and as a fan of his other films (even the sadly forgotten Some Kind of Wonderful and the criminally underrated Uncle Buck), I expected the same precision he always exhibits. If there’s one thing Hughes knows how to do, it’s create characters that are likeable both despite their flaws and because of them.

I know a lot of people find these characters interesting, but I cannot possibly fathom how that is. Sure, Ringwald is dependably game, playing a slightly less complicated and more mouth-breathing version of the doe-eyed innocent she always plays—the girl right on the cusp of true love and true hymen breakage—even if the film gets her class status completely wrong. As someone who grew up in a similar socioeconomic situation to Andie, I’m calling bull on the ways in which Hughes depicts lower-middle class dynamics. Andie is meant to come from salt-of-the-earth folks, or Harry Dean Stanton (the male equivalent of Frances McDormand, our saltiest thespian) wouldn’t be playing her father and she wouldn’t be making her own dress to go to the prom. The implication is that she can’t afford to go otherwise (which is understandable because prom is expensive), but then why does she have her own phone line? Somebody better call up Michael Moore, because it turns out that the working poor have got it good.

But Andie is hardly the problem of the film, and you won’t hear two bad words about Molly Ringwald come out of this mouth. The bigger issue, for me, is that every man that surrounds Andi is a total jerk or nincompoop, and the only other character worth spending time with is James Spader’s Steff, an entitled prep with his nose forever aloft in scorn of those who aren’t also loyal Lacoste shoppers. If the movie were about him and written by Bret Easton Ellis, it might have been worth watching, but unfortunately we have to watch his wetnap best friend and a guy named after a duck fight over a girl who is clearly too good for either of them.

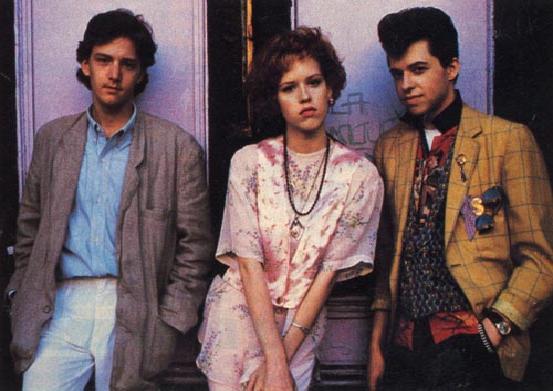

Let’s start with Blaine, the former wet one. Blaine is like a watered-down facsimile of every John Hughes dream guy, and his character is so similar to Jake Ryan that I forget Blaine wasn’t played by Michael Schoeffling. However, Schoeffling and his dangerously sharp facial structure actually exude charisma, whereas Andrew McCarthy’s bland presence has a way of floating into the background. McCarthy is beautiful to look at, and the camera loves his face, but he’s beautiful in that J.Crew model way, where he’s meant to be more a room accessory than a human being. McCarthy is designed to blend in, and there’s not a lot of room for personality in that.

Because McCarthy’s character is so underwritten, that leaves Jon Cryer to do all of the emotional heavy lifting, a phrase I can’t believe I just wrote. Folks, this is the man whose major acting technique is to screech when he gets excited, hardly the stuff of James Lipton legend. And beyond Cryer’s extremely limited range, the larger issue is the character of Duckie, the virulently unlikeable mutt that the movie insists is a winsome romantic underdog. In general, I adore unlikable characters, and movies that challenge the traditional ways in which we root for the protagonist. Last year’s Young Adult was a prime example of that, a film whose toxic Mavis was so horrendously unlikeable that writer Diablo Cody dared you to identify with her. However, Charlize Theron’s performance was so effortless in imagining the inner life of a post-high school Promzilla that you couldn’t help but become invested in her.

Other movies have done a fantastic job of this, but to do so, you have to embrace the character’s douchiness and find the beating heart inside. Alejandro Amenabar’s Abre Los Ojos did a flawless job of this, arguing that just because a entitled rich guy can’t face up to the consequences of his action doesn’t mean that he isn’t beyond redemption. But American films have a big problem with this, believing that audiences can only handle characters who are traditionally likeable, and the remake of Amenabar’s masterpiece (Vanilla Sky) proved that by making the lead into a Duckie character and nearly killing the entire purpose of the film. Another great example of the Duckie problem is Reality Bites, a movie that seems very confused about who is the villain and who is the hero. When Winona Ryder ends up with the arrogant, petulant Ethan Hawke instead of the patient, loving Ben Stiller, you can’t help but think she made the wrong choice.

But in Pretty in Pink, the film presents no real right choice. Andie could settle down with the needy, emotionally abusive Duckie (who is too selfish the entire film to try to be even a little bit happy for his best friend’s romantic bliss) or the vacant Blaine. Of course, Andie doesn’t wind up with Duckie at the end, because Hughes’ film isn’t smart enough to drive itself that much off the cliff, and the movie presents it as a lesson learned for our dear Duckie—namely, that you can’t just want the girl, you have to deserve her. Like the similarly interminable Police, Adjective (which may take the cake as the dullest film I’ve ever seen), the movie may present a reason to exist in the last five minutes, but it doesn’t mean that makes up for the previous hour and a half, or make you care anymore about the conclusion. With prom options like Duckie and Blaine, I’d rather just go stag.