Culture

The Man Who Invented Beer: Greene King’s Abbot Ale

Every Wednesday in The Man Who Invented Beer, Adam Cowden runs down the latest developments in the world of craft beer, usually with a history lesson for flavor.

Anyone who has the opportunity to “study” abroad in Europe and doesn’t take it is a damn fool. When else will you have the opportunity to throw up in front of American-themed bars in a different country every weekend, all on your parents’ dime? In all seriousness, though, studying abroad can be pretty enriching even if you never make it to class. (Just stay away from those American-themed bars, for God’s sake.) Read up on the history of any American craft brewer, and chances are that somewhere along the line one of the founders acquired a taste for beer while studying in Europe. More than a little bit of my semester in London was spent in the pub carefully studying the rich, wonderful and fascinating subject of English beer, and one of my favorite topics was Greene King’s Abbot Ale. Recently, I was reminded of my love for this subject after a rare sighting of a four pack of Abbot Ale in 16 oz. pub cans. Curious as to how the export version would compare to the local brew served in pubs across the pond, I decided to take the hefty price tag on the chin and pick it up.

What’s the story?

Greene King traces its brewing heritage all the way back to the cerevisiarii of the town of Bury St. Edmunds. These were 11th-century servants of the Abbot recorded in the famous Domesday Book, who brewed ale for the town’s great Abbey. To this day, Greene King supposedly draws their liquor (water used for brewing) from the same chalk wells used by these 1,000 year old brewers. It wasn’t until 1799, however, that Benjamin Greene laid the foundations for what is now the Greene King brewery in Bury St. Edmonds. His house, located right around the corner from the brewery, had once been the home of the town’s last Abbot, Abbot Reeve, for whom the brewery’s flagship ale is named.

Why should I drink it?

Prior to the 1950s, beer was primarily stored and transported in wooden barrels called casks. Bottled beer had surfaced in the 17th century, but its then-prohibitive price meant that it was primarily limited to the upper class who wished to drink outside of public houses. Cask ale was unfiltered, unpasteurized and free from forced carbonation. After Louis Pasteur invented his method for flash-sterilization in the 19th century, it became common practice to pasteurize beer in order to prolong its shelf life, though this did not catch on immediately in the cool, quickly-drinking environment of Great Britain. It wasn’t until the invention of the keg in the 1960s (the descendant of the metal cask of the 1950s) that this began to change; the keg’s unique shape and design allowed for all of its contents to be forced out using pressurized gas, and this required that the sediment be filtered out of the beer before its transfer to the keg. (The old cask design had allowed for the sediment to remain trapped at the bottom.) By the 1970s, nearly all of the beer in Britain was filtered, pasteurized and force-carbonated, leading to a demand for what certain consumers considered “real” ale. The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) was founded in Great Britain in 1971, and it is this organization that is largely responsible for saving cask-ales from extinction.

CAMRA defines real ale as “a natural product brewed using traditional ingredients and left to mature in the cask (container) from which it is served in the pub through a process called secondary fermentation.” It is also free from non-natural carbonation, which CAMRA claims “creates an unnaturally fizzy beer rather than the gentle carbonation produced by the slow secondary fermentation in a cask of real ale.” Real ale can be cask-conditioned or bottle-conditioned; the main requirements are that it is active (contains yeast), unfiltered, and naturally carbonated. Cask-conditioned ale has a shorter shelf-life than keg beer and requires much more attention from the pub. It must be stored at “cellar temperature” (54 -57 degrees F), allowed to ferment for the proper amount of time (this varies depending on the beer) and drawn up from the cellar using a hand-pulled suction pump. You can spot a cask ale in a British pub by the distinctive hand pumps, which are usually grouped together separately from the keg taps. An expert bartender at a quality pub will fill up your pint glass with two long pulls of the pump, plus one quick one to top it off. In some cases, the beer is served directly from the cask using simple gravity dispensation. (This is sometimes fashionable, as it creates an “old-timey” atmosphere.)

After all of this discussion, you may be disappointed to learn that the Abbot Ale available in the U.S. is not “real ale.” It is filtered, pasteurized and carbonated (in the case of the can, using a nitrogen widget), meaning that it meets none of CAMRA’s requirements for real ale. In order to get the real thing, you’ll have to travel to the U.K., where you’ll see the Abbot Ale hand pump sitting alongside the other cask ales behind the bar at many of the country’s thousands of pubs. The canned variety available over here is nonetheless one of the best imitations of a real cask ale that I’ve had, especially if you allow it to sit for a bit and warm up to just above room temperature. You’ll also be supporting a great English brewer that produces one of the best widely-available examples of “real ale” that you can find in England today.

What does it taste like?

Creamy, smooth and complex. Some citrusy, flowery aromas waft up from the glass, but the flavor is predominately buttery, toffee-like malty sweetness. It finishes with just enough hop bitterness to balance it out, and the bitterness is definitely of the smoother, earthy English-hop variety, rather than the pine-y American variety most of us are used to. There’s also a considerable amount of minor tastes that pop up in there, though I’d be lying if I said I could pick them all out. The alcohol content is noticeable but not overwhelming, and the beer finishes with a lingering sweetness, rather than bitterness. It’s hard to compare this beer to an American-style pale ale, with which it has little in common, but if you’ve ever had Boddington’s (probably the most widely available English pub-style ale stateside), it’s not unlike a richer, fuller-tasting version of that. I actually thought it tasted most similar to an old Binny’s favorite called Wexford Irish Cream Ale, which (as I realized upon further research) is also produced by Greene King!

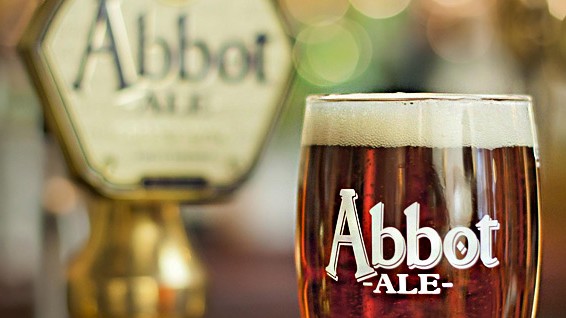

Abbot Ale is exported in a nitro-can (thanks, Guinness!) and served on a nitro-tap in order to feign a cask-like feel. The soft nitro-carbonation is a pretty good imitation of the natural carbonation that occurs in a cask as a result of fermentation, though the nitro-carbonation does lend the beer a silky, creamy feel that isn’t really present in the cask version. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; if you like the velvety feel of a mouthful of Guinness but not the dark-roasted flavor, you might just fall in love with this beer. The nitro also gives the beer a beautiful pour (love those little cascading bubbles) and an appealingly creamy white head that complements the golden color very well. This is actually one of the best-looking beers I’ve ever had; the slightly-hazy, deep amber coloring is just so appetizing that I think it actually tricks you into thinking it tastes even better than it already does.

Should I try it?

It’s a luxury that comes with a larger price tag over here in the States (my four-pack was around $13), but if you want to get an idea of what an excellent English pub ale tastes like, or if you already know and are looking to recapture the experience, the extra few dollars are well worth it. In my opinion, it’s the closest you’ll get to sipping a real, hand-pulled, cask-conditioned ale without dropping hundreds of dollars for a flight to London. Though if you have the money and time, by all means go, and don’t waste your time gawking at churches and castles. They don’t serve beer there.

Rating: 8/10

[…] which means it’s unfiltered, warmer, and non-forced carbonated (if you want a refresher on cask ales, head on back to my Abbot Ale review). Why should you care? Well, these beers’ unfiltered, cloudy […]